1. Religion in Facts vs. Declarations

Benevolence or Power Consolidation? Christianity, particularly in its institutionalized forms, has often positioned itself as a force for peace, charity, and moral guidance. However, a closer examination of historical events reveals a more complex picture.

The Crusades (1096–1291): Initiated by the Catholic Church, these military campaigns aimed to reclaim Jerusalem from Muslim rule. They resulted in significant loss of life, cultural destruction, and long-standing animosities between Christian and Muslim communities. The First Crusade alone led to the massacre of thousands of Jews and Muslims in Jerusalem.

The Inquisition (12th–19th centuries): The Catholic Church established tribunals to identify and eliminate heresy. These inquisitions led to the torture and execution of thousands, particularly during the Spanish Inquisition, where suspected heretics were burned at the stake.

Colonialism and Missionary Activity: European colonial powers often justified their conquests through a 'civilizing mission', which included the spread of Christianity. This led to the suppression of indigenous cultures, forced conversions, and the establishment of systems that prioritized European religious norms over native traditions.

Lausanne Movement While Christianity has undeniably contributed to art, education, and social services, these contributions were often intertwined with efforts to consolidate power and control over diverse populations.

Islam: Conquest, Social Control, and Institutionalized Authority Islam, emerging in the 7th century, rapidly expanded across the Middle East, North Africa, and beyond, primarily through military conquest, coercion, and political centralization. Its spread was not a benign cultural influence but a systematic imposition of religious authority over diverse populations.

Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphates (632–750): Following the death of Prophet Muhammad, the Islamic empire expanded through military campaigns. Conquered peoples were often subjugated, taxed (jizya), and subjected to Sharia law, which codified religiously enforced hierarchies and restricted freedoms for non-Muslims. Resistance or dissent was frequently punished.

Al-Andalus (711–1492): While some narratives suggest cultural coexistence, the reality involved systematic enforcement of Islamic authority. Non-Muslims faced legal restrictions, forced conversions occurred, and periods of persecution were common. Intellectual activity and scientific progress existed, but always under religious oversight, limiting free inquiry and independent thought.

Gender and Family Control: From the earliest caliphates, Islamic law restricted women’s autonomy in marriage, divorce, inheritance, and public life. Polygyny, strict dress codes, and male guardianship reinforced patriarchal control. Family structures institutionalized obedience to male authority and religious norms, with corporal or legal sanctions for dissent.

Suppression of Dissent: Apostasy, blasphemy, and criticism of religious authorities were legally punishable, sometimes by death. This created an environment where obedience and conformity were enforced, limiting social innovation and freedom of thought.

Social Hierarchies: Non-Muslims and lower-status groups were subjected to systemic discrimination, including taxation, restricted rights, and limited political participation. Religious law was the primary instrument of maintaining social stratification.

Modern Political Islam: Attempts to create “Islamic democracy” are historically and doctrinally contradictory. Governance based on religious law inherently prioritizes obedience to religious authorities over popular sovereignty, undermining true democratic principles. Islamist movements seeking political power have often resulted in authoritarian regimes, suppression of free expression, and enforcement of social hierarchies.

Summary: Islam’s historical trajectory demonstrates a consistent pattern of conquest, hierarchy, social control, gender and minority restrictions, and suppression of dissent. The notion of peaceful coexistence or democratic adaptation is often a modern rationalization, not reflective of the religion’s foundational doctrines or historical practices.

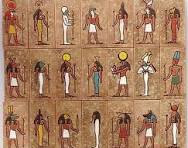

Inclusivity and Cultural Pluralism Polytheistic religions, practiced in ancient civilizations such as Greece, Rome, and Egypt, often embraced a multiplicity of deities and cultural practices.

Cultural Integration: Polytheistic societies were generally inclusive, allowing for the integration of various deities and practices. This inclusivity facilitated cultural exchange and the blending of traditions.

Political Legitimization: Rulers often associated themselves with deities to legitimize their authority. While this provided a unifying cultural framework, it also reinforced hierarchical structures and the centralization of power.

Decline and Transformation: The rise of monotheistic religions, particularly Christianity, led to the decline of polytheistic practices. The transition was often marked by the suppression of polytheistic traditions and the imposition of new religious norms. Polytheism's emphasis on inclusivity and cultural pluralism allowed for diverse expressions of belief and practice, but it also intersected with political structures that could limit individual autonomy.

Power Structures and Human Autonomy When comparing the historical impacts of these religious systems, several patterns emerge: Centralization of Authority: All three religious traditions have been associated with the centralization of authority, whether through the Church in Christianity, the Caliphate in Islam, or the divine right of kings in polytheistic societies. This centralization often limited individual autonomy and dissent. Cultural Suppression: The spread of these religions frequently involved the suppression of indigenous cultures and practices. This was particularly evident during colonial periods and in regions where religious conversion was enforced.

Each tradition has been linked to the establishment and maintenance of social hierarchies. In Christianity, this was evident in the feudal system; in Islam, through the caliphate structure; and in polytheistic societies, via caste or class systems. While these religions have contributed to cultural and intellectual developments, their historical trajectories also reflect patterns of control and limitation of human autonomy. This analysis provides a critical examination of the historical impacts of Christianity, Islam, and polytheism, highlighting the complexities and contradictions inherent in their roles in society. The next section will delve into the role of religion in education, exploring how religious doctrines have influenced educational systems and the implications for human development.

Islamic Educational Approach – Historical Overview

Early Islamic Education (7th–10th centuries)

Key Facts:

Quran as Foundation: Education in early Islam was primarily centered on memorizing and understanding the Quran.

Mosque Schools (Madrasa/Masjid Classes):

- Early educational gatherings were often in mosques.

- Students learned Quranic recitation, basic literacy, and moral/religious instruction.

Prominent Figures:

- Prophet Muhammad (570–632 CE) emphasized learning and literacy; reportedly said: “Seek knowledge even if you go to China”.

- Curriculum: Focused on Quran, Hadith (sayings of the Prophet), basic Arabic literacy, and religious obligations.

Restrictions / Facts of Early Limitations:

Education was mostly religious; secular sciences were secondary.

Initially, girls’ education was limited; the focus was mainly on male students for religious instruction.

Access depended on community affiliation and financial resources.

Medieval Islamic Education (10th–15th centuries)

Establishments / Institutions:

Madrasa System:

- First formal madrasas appeared in the 10th century (e.g., Nizamiyya in Baghdad, founded 1065 by Nizam al-Mulk).

- Offered structured curriculum, scholarships, and trained religious scholars (ulama).

Private Teaching: Scholars also offered private lessons in homes or small schools.

Curriculum Expansion:

Religious studies remained primary (Quran, Hadith, Fiqh – Islamic jurisprudence).

Gradually included mathematics, medicine, astronomy, logic, philosophy, especially in cities like Baghdad, Cordoba, Cairo.

Restrictions / Facts:

Women had limited access; elite women sometimes studied at home with private tutors.

Non-Muslims could run schools but usually under community or state restrictions.

Secular sciences were sometimes seen as complementary to religious knowledge, but not universally encouraged.

Early Modern Period (16th–19th centuries)

Key Facts / Establishments:

Ottoman Empire: State-supported madrasas existed in cities like Istanbul. Curriculum: Quranic studies, jurisprudence, theology, logic, arithmetic, history.

South Asia (Mughal Empire): Large network of madrasas and Quranic schools; notable institutions included Darul Uloom Deoband (founded 1866).

Curriculum Reform:

Some madrasas started introducing modern subjects like medicine, astronomy, and grammar.

Restrictions / Facts:

Gender segregation persisted; formal female madrasas were rare.

Non-religious education was often limited in scope and controlled by religious authorities.

Modern Islamic Education (20th–21st centuries)

State Reforms:

Countries like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan established government-supported madrasas and Islamic universities.

Examples: Al-Azhar University (Cairo) modernized curriculum to include sciences, law, and international studies.

Integration with Secular Education:

Many modern madrasas include mathematics, science, and languages alongside traditional religious studies.

Global Spread:

Islamic schools now exist worldwide, from Indonesia to Europe and North America.

Restrictions / Facts:

Some countries limit female enrollment in traditional religious schools (though this is changing in many regions).

Curriculum is sometimes tightly controlled to conform with national or religious laws.

Political or sectarian tensions sometimes influence what can be taught in religious schools.

Key Principles of Islamic Educational Approach

- Religious Centrality: Quran, Hadith, Fiqh as core studies.

- Moral & Ethical Instruction: Education is holistic — intellectual + moral development.

- Teacher-Student Relationship: Emphasis on respect, mentorship, and oral transmission.

- Community-Based Learning: Mosques, madrasas, and private tutors serve as learning hubs.

- Adaptability: Over centuries, curricula expanded to include mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and modern sciences.

Based on human rights we may comes to summary:

- Private practice: Individuals can believe what they want, in private.

- Public propagation restricted: No preaching, proselytizing, or religious activism outside designated private spaces.

- Dedicated spaces only: Religious services in specific, registered areas.

- Penalties for public propagation: Enforcement limited to public acts, not belief itself.

Religios And Education

1. Religiology: Definition

Religiology is the scientific study of religion as a human and social phenomenon. It examines religious beliefs, doctrines, rituals, texts, and institutions without promoting or practicing any faith. Unlike theology, which interprets religion from within a faith perspective, religiology is descriptive, analytical, and comparative.

- It studies religions historically, sociologically, psychologically, and anthropologically.

- It analyzes the social, political, and cultural impact of religions, including their role in shaping laws, ethics, and hierarchies.

- Religiology recognizes the diversity of belief systems — from monotheism and polytheism to animism — and evaluates their influence on human societies objectively.

Key Point: Religiology is not a tool for indoctrination; it is a discipline for understanding religions as social and cultural forces, not as sources of moral or divine authority.

2. Religiology as Science

Religiology qualifies as a science because it adheres to empirical, analytical, and methodological principles:

- Empirical Observation: Religions are studied through historical records, texts, rituals, and material culture. Evidence is gathered systematically.

- Comparative Method: Scholars examine similarities and differences between religious systems, identifying patterns in doctrine, social control, gender roles, and hierarchy.

- Critical Analysis: Claims of moral authority or divine truth are not accepted on faith; instead, religions are evaluated for their societal consequences and internal logic.

- Predictive and Explanatory Power: Religiology explains phenomena such as religiously motivated conflicts, social stratification, and gender oppression, providing insight into human behavior under religious influence.

Examples of Scientific Insights:

- Monotheistic religions often centralize authority, enforce hierarchical obedience, and limit dissent.

- Polytheistic systems generally allow more pluralism, flexibility, and individual autonomy.

- Religious doctrines historically correlate with social restrictions, such as gender inequality, family control, or political oppression.

3. Basic Requirements for Educational Processes

When religiology is included in education, certain principles must be strictly followed:

- Secular Curriculum: Religious study must remain descriptive, analytical, and non-partisan. Students should learn about religions as social phenomena, not as moral prescriptions.

- Critical Thinking Emphasis: Students must evaluate religious texts, doctrines, and institutions critically, understanding historical and contemporary impacts without being influenced to believe.

- Comparative Perspective: Curricula should include multiple religious systems (Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, polytheism, secular belief systems) to illustrate patterns of social control, hierarchy, and freedom.

- Ethical Neutrality: Educators cannot promote any religious worldview or favor any group. The goal is knowledge and understanding, not conversion or moral instruction.

- Documentation and Evidence: Claims about religion must be backed by historical records, sociological studies, and scientific research, not anecdotes or doctrinal assertions.

4. Education Must Strictly Prohibit Religious Propagation

A central principle of modern education is the absolute separation of teaching from religious indoctrination:

- No Participation in Faith Practices: Students are not required or allowed to participate in prayers, rituals, or religious ceremonies.

- No Promotion of Belief Systems: Teachers cannot advocate religious truth claims, moral imperatives, or divine authority in classroom instruction.

- Prevention of Social Pressure: Religious influence can create hierarchies, discrimination, or peer pressure, undermining equality and freedom of thought.

- Legal and Ethical Precedents: International human rights frameworks (e.g., UNESCO, UN Declaration on Human Rights) recognize the right to secular, unbiased education and protection from religious coercion.

Conclusion: Religions can be studied scientifically through religiology, but educational processes must never serve as a platform for propagation or indoctrination. Secular, critical, and comparative study ensures students develop independent thought, cultural literacy, and social autonomy, free from the historical patterns of control that religious institutions have imposed.