As we mentioned, our choice of the initial point is taken from well-established states...

As recognizable states, we may identify in the Chinese historical retrospective of the so-called antiquity two prominent empires.

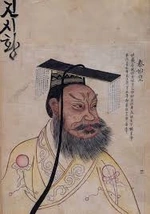

⛩️ The Qin Empire (Qin Dynasty, 221–206 BCE) — the first unified imperial state in Chinese history. This state will serve as our primary object for descending analysis, tracing the cultural origins of the civilisation. Founded by Qin Shi Huang, who consolidated the Warring States territories, the Qin introduced full centralisation of bureaucracy, and standardised weights, measures, script, and law. Functionally, Qin created the template of what “empire” means in the Chinese context — centralised command from the Emperor through administrative prefectures.

⛩️ The Han Empire (Western Han, 206 BCE – 9 CE; Eastern Han, 25 – 220 CE) — the successor and stabiliser of the Qin model, yet more sustainable and culturally rich. Han governance introduced Confucian bureaucracy, the early roots of civil service examinations, and a balance between imperial central authority and local administration. It expanded territorial control into Central Asia via the Silk Road, making it the second great imperial consolidation in Chinese history.

⛩️ The Zhou Context (c. 1046–256 BCE)

Zhou dynasty, outstanding in its achievements of assembling dozens of territories, and finally uniting them into one single state under the sole power of the emperor. Nevertheless, there was not an instant path — the consolidation period took more than seven and a half centuries.

– The Zhou dynasty followed the Shang and introduced the idea of the Mandate of Heaven — that moral legitimacy justified rule.

– Early Zhou governance (Western Zhou, 1046–771 BCE) was feudal: power distributed among hereditary lords.

You think all things would be easy? We thought so too... But, this fractioning required more detail.

The Eastern Zhou lifetime was predominantly devoted to conquest activity — and not without achievements:

– Spring and Autumn (771–481 BCE): Dozens of semi-autonomous states, nominally under Zhou kingship. Local rulers began reforms, built armies, and developed bureaucracies.

– Warring States (481–221 BCE): Seven major powers (Qi, Chu, Yan, Han, Zhao, Wei, Qin). Warfare drove centralisation and technological progress.

During the Warring States, the state of Qin, in the far west, gradually strengthened through agricultural reform, military innovation, and strict legalist governance (notably under Shang Yang).

✏️ Transition: From Zhou Disunity to Qin Unification

The Zhou kingship lost practical control; its authority survived only symbolically. Qin adopted Legalism, replaced hereditary aristocracy with appointed officials, and imposed standard taxation and conscription. By exploiting geography (fertile Wei Valley, defensible terrain) and reforms in land use and military discipline, Qin became the most efficient and centralised state. In 221 BCE, Qin Shi Huang defeated the last rivals, ending the Zhou world and founding the first imperial China — the Qin Empire.

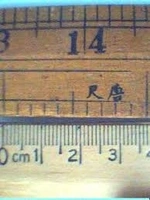

Maesurement Units Of Qin Dynasty

As we already know, the Qin governing period was characterized by the centralization of all state-managing functions, including taxation and metrological standardisation. These conditions define the necessity of reviewing the measurement system of the period.

| Qin Unit | Chinese (秦制) | Relation | Approx. Metric Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhi (指) | Finger breadth | — | ≈ 0.019 m | Smallest unit used on some rods |

| Cun (寸) | Inch | 1 cun = 10 zhi | ≈ 0.023 m | Basis for small crafts, tools |

| Chi (尺) | Foot | 1 chi = 10 cun | ≈ 0.231 m | Standard Qin ruler unit |

| Zhang (丈) | Fathom | 1 zhang = 10 chi | ≈ 2.31 m | Human-scale measure, architecture |

| Bu (步) | Pace | 1 bu = 6 chi | ≈ 1.39 m | Used for field and road layout |

| Li (里) | Chinese mile | 1 li = 300 bu | ≈ 415 m | Road & land surveying standard |

⛏️ Archaeological evidence:

- Bronze measuring rod from Fuling Tomb (Xi’an, 221 BCE) → 1 chi = 23.1 cm

- Fangmatan bamboo slips (Tianshui, Gansu) confirm identical ratios and notation

- Standardized road ruts near Xianyang show cart axle widths ≈ 1.5 m, matching Qin chi–bu

| Qin Unit | Chinese (秦制) | Relation | Approx. Modern Equivalent | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhu (銖) | — | — | ≈ 0.65 g | Base weight for coins & herbs |

| Liang (兩) | Tael | 1 liang = 24 zhu | ≈ 0.015.6 kg | Coin and trade standard |

| Jin (斤) | Catty | 1 jin = 16 liang | ≈ 0.249 kg | Everyday market weight |

| Jun (鈞) | — | 1 jun = 30 jin | ≈ 7.47 kg | Heavy commercial measure |

| Shi (石) | — | 1 shi = 4 jun ≈ 120 jin | ≈ 29.9 kg | Bulk grain & taxation unit |

⛏️ Archaeological evidence:

- Bronze weights with inscriptions “Qin liang” unearthed at Xianyang, Yangling, and Shuihudi — all consistent at ~15.6 g per liang.

- Banliang coins (half-liang denomination) weigh ≈ 7.8 g, confirming state-regulated mint ratio (½ liang ≈ 7.8 g).

- Stamped Qin “Jin” stone weights in Xi’an Museum show perfect proportional scaling.

| Qin Unit | Chinese (秦制) | Relation | Approx. Modern Equivalent | Common Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheng (升) | — | — | ≈ 0.200 L | Base liquid & grain measure |

| Dou (斗) | — | 1 dou = 10 sheng | ≈ 2 L | Daily trade & rations |

| Hu (斛) | — | 1 hu = 10 dou | ≈ 20 L | Storage, taxation, granaries |

| Shi (石)** | — | 1 shi = 10 hu | ≈ 200 L | Major state grain unit (same term as weight “shi” but contextually distinct) |

⛏️ Archaeological evidence:

- Bronze “Qin hu” and “dou” vessels excavated at Xi’an and Fufeng sites, with inscribed calibrations consistent with 10:1 ratios.

- Shuihudi bamboo slips (c. 217 BCE) contain inventory tallies using these units.

- Ceramic grain jars found at Terracotta Army pits also inscribed with “Shi” (石) for bulk accounting.

The authors suggest that the system’s internal interrelations may serve as a useful basis for a comprehensive understanding of the period’s metrological standards.

| Category | Base | Multipliers | Qin → Metric (approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 1 chi | 10 cun = 1 chi → 10 chi = 1 zhang | 1 chi ≈ 0.231 m |

| Weight | 1 liang | 24 zhu = 1 liang → 16 liang = 1 jin | 1 liang ≈ 0.0156 kg |

| Volume | 1 sheng | 10 sheng = 1 dou → 10 dou = 1 hu | 1 sheng ≈ 0.2 L |

The methodologically grounded derivations of all the above parameters, established with respect to the corresponding artefacts, are hereby presented to the reader’s attention.

| Site | Find Type | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Fangmatan (Gansu) | Bamboo slips with measurement records | Confirms Qin administrative math system |

| Shuihudi (Hubei) | Qin legal texts and inventory slips | Defines unit relations & taxation |

| Xianyang (Shaanxi) | Bronze weights and standard rods | Physical standards of chi & liang |

| Terracotta Army site | Tool inscriptions & cart dimensions | Applied standards in engineering |

| Yangling Mausoleum | Grain measures with inscriptions | Verifies hu–dou–sheng volume scaling |

This article is part of a long-read publication. [Go to the full version →]

This chapter devoted to two cultures, Babylonia and Persia, and here uncover why...

And here the place we should turning backward, to culture, already passed but under other angle...